Diet Soda Does Not Cause Diabetes

You may have seen very scary headlines in the past couple weeks, claiming that diet soda causes strokes. As usual, these headlines don't fully reflect the study results, and we're here to break down that study in depth.

First things first: CORRELATION not CAUSATION

First, the study under review is an observational study, meaning that there is no experiment being done (like assigning a group to drink diet soda, and another one to drink water); rather it involves observation of lifestyles and health outcomes.

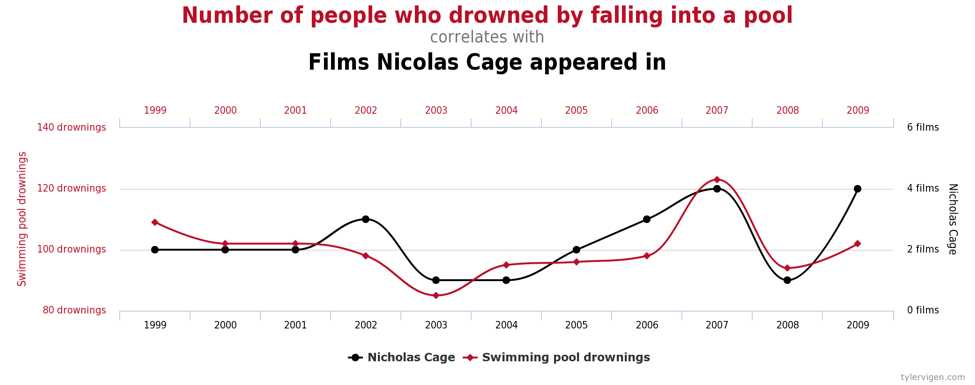

Therefore, you can only find correlations, and cannot establish a cause and effect relationship. There's a fairly high likelihood of unaccounted factors affecting the study outcomes, and correlations can sometimes be strong but misleading. For example, check out the graph below, which shows a strong correlation between the number of movies Nicholas Cage has appeared in and the number of people who drowned in a pool for a given year. The data looks very suspicious for Mr. Cage, but at the end of the day it's very unlikely that these movies have caused people to drown, no matter how bad they are.

But this does not mean that we should automatically discount a study simply because it's an observational one. There are a lot of things you can't conduct an experimental study on because it would be impractical or unethical, such as randomizing people to a heavy-cigarette-use group to see how many get lung cancer. Observational studies are often used to generate hypotheses which can be tested in further human trials or animal studies.

Observational studies cannot establish a cause and effect relationship. Memorize that and never forget it. However, observational studies are still an important piece of the puzzle and they're worth examining in detail.

What did the researchers find?

This study looked at the relationship between both sugar-sweetened and artificially-sweetened beverages and the incidence of strokes and dementia. It tracked ~4,000 people from Massachusetts from 1991 until 2014 to see how many sugar-sweetened drinks and artificially-sweetened drinks each person drank, along with how many individuals were diagnosed with strokes or dementia.

Because factors such as smoking, lack of physical activity, and excess caloric intake could increase the risk of having a stroke or developing dementia, the researchers adjusted for these covariates.

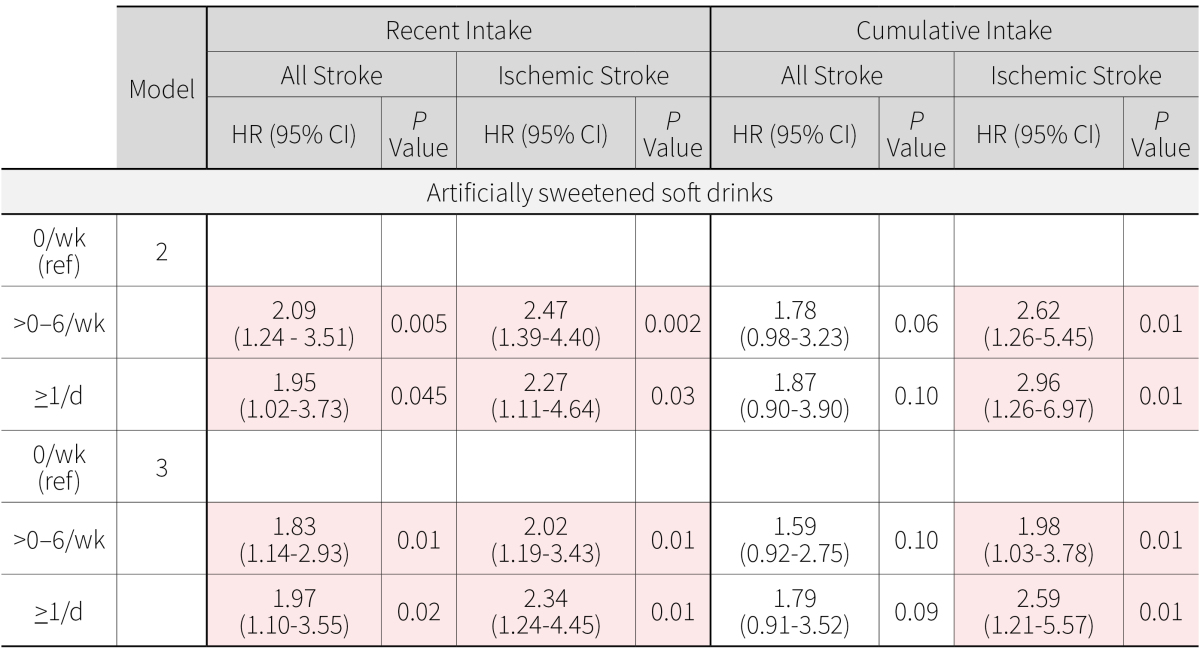

The headline-grabbing result was pretty stark: people with a cumulative intake of more than one artificially-sweetened beverage per day were 2.96 times more likely to be at risk for an ischemic stroke and 2.89 times more likely to be at risk for developing dementia, compared to people who did not drink any sweetened beverages. Those who drank sugar-sweetened beverages didn't see an increased risk.

After following ~4,000 people over fourteen years, researchers found that people who consumed more than one artificially-sweetened beverage per day were around three times more likely to experience an ischemic stroke or dementia, while sugar-sweetened beverage drinkers didn't have an increased risk.

Are the results as strong as they appear? Probably not.

All observational studies have this limitation, but it's worth repeating: you simply cannot adjust for all possible covariates that might impact the outcomes (stroke and dementia) and also be related to the exposure (drinking artificially-sweetened beverages). For example, people who drink diet soda may also be, on average, more likely to do yo-yo diets, have higher stress levels, or have any of other countless behaviors that might theoretically be tied to greater risk for disease.

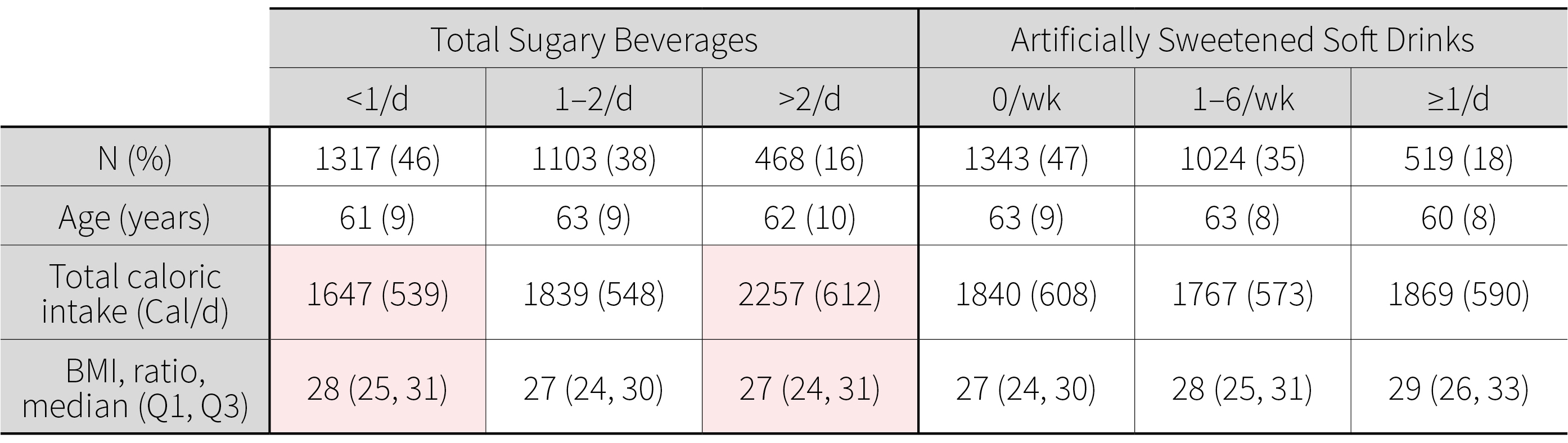

Another problem with the study can be seen in the highlighted numbers below: the group that consumed the most calories had a lower BMI than groups that consumed fewer calories. Very strange. This may be due to random variation, but it's also possible that the Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs) used by the researchers just weren't very accurate. And indeed, FFQs are not very reliable at determining what an individual has eaten over a long period of time, especially in older individuals.

Moreover, in the table below, check out all the effect sizes. They're not all particularly large and it's possible that they may deviate depending on what was adjusted for in a particular model. Some researchers have proposed that instead of adjusting only for a few covariates, that all possible combinations of covariates be adjusted for and the median of that be presented instead. Given that the study didn't do this and was not preregistered, much of these results can be taken as exploratory analyses rather than confirmatory analyses.

The food frequency questionnaire used in this study may not have been very accurate. But more importantly, the study adjusted for several covariates and presented only a few models, and the study was not preregistered. Thus, many of these results may be taken as exploratory associations.

So is diet soda being unfairly blamed? Maybe not.

Regardless of study limitations, if you drink a ton of diet soda, it may be wise to think a bit more about this study. Why? Well, the study showed a strong association between artificially-sweetened beverages and stroke/dementia (albeit with major statistical limitations as discussed above), but did NOT show an association between sugar-sweetened beverages and stroke/dementia.

And the authors weren't industry shills out to prove a certain food product is healthier than others -- the funding was government-provided, and there were no financial disclosures listed. This is actually somewhat important, as studies on artificially-sweetened beverages that are funded by industry tend to be more biased.

So are people who drink diet soda really that different from those who drink regular soda … enough to explain away this association? Nobody knows for sure, but what we do know is that sugary soda is strongly linked to things that increase your chances for having a stroke (like type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure) and dementia (like a generally poor diet).

Artificial sweeteners though are less clearly linked to chronic disease, at least mechanistically. They don't appear to spike insulin, and the strongest evidence of these sweeteners causing altered glucose homeostasis (and increased food intake) is in … fruit flies. And even though there are some reviews with alarming titles like "Artificial sweeteners produce the counterintuitive effect of inducing metabolic derangements", the evidence actually cited in the reviews is much more mixed than the titles would lead you to believe.

But overhyped titles don't mean you should totally ignore potential risks. Two of the most complex research areas are the human gut, and the human brain, and it turns out that some artificial sweeteners may potentially (keyword: potentially … nobody really knows at this point) impact our gut microbiota and the sweet-taste-processing of diet soda drinkers.

Other than being observational in nature, this study had serious statistical limitations, which limit its applicability. So no, "diet soda causes strokes and dementia" is not accurate.

That being said, a lack of strong evidence doesn't mean everything. We only know what the research tells us, and the research tells us there's a lot about artificial sweeteners we don't know, such as how they impact different gut microbiota. And since there are multiple different artificial sweeteners used in different beverages (aspartame, sucralose, etc), it's going to be a long time until we form a concrete picture on any one of them.

Want more of these kinds of in-depth analysis? For any professional, it's important to stay on top of the latest research, and our monthly digest helps you do just that. Click here to check out the Nutrition Examination Research Digest.

Diet Soda Does Not Cause Diabetes

Source: https://examine.com/nutrition/does-diet-soda-cause-strokes-and-dementia/

0 Response to "Diet Soda Does Not Cause Diabetes"

Post a Comment